Attack of the Mutant Telephones

Home computers in the 80s

You are in a comfortable tunnel-like hall. You see:

A ZX Spectrum.

A curious map.

A small, hairy-footed humanoid.

> Examine Spectrum.

I don’t see one of those here. The small, hairy-footed humanoid says “Plugh.”

> Examine ZX Spectrum.

You examine the ZX Spectrum.

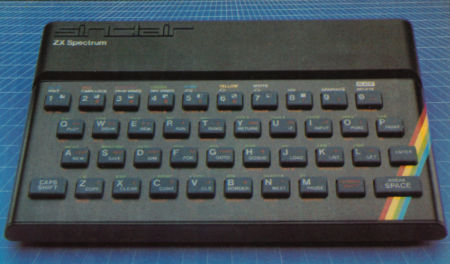

You see a small, sleek black slab of rubber-keyboarded technology. Developed by Sinclair Research in 1982, the ZX Spectrum is the height of 1980s consumer technology. In a decade that saw more households than ever before owning a colour television, a hi-fi, and a video recorder, the ZX Spectrum taught a whole generation of kids how to program computers. Or play games. (Mostly it was to play games.)

What do you want to do?

> Play a game.

Play a game with what?

> With the Spectrum.

I don’t see one of those here. The small, hairy-footed humanoid says “Plugh.”

> With the ZX Spectrum.

Do what with the ZX Spectrum?

> Play a game with the ZX Spectrum.

You play a game with the ZX Spectrum.

What game would you like to play? You can play:

> Manic Miner.

Are you sure you don’t want to play The Hobbit?

> No, play Manic Miner, okay? And if that small, hairy-footed humanoid says “Plugh” once more, punch him!

Computers in the 1980s were different.

For a start, they weren’t called computers. They were called “home computers”, “microcomputers”, or “micros”, to differentiate them from the larger, more serious machines (known as mainframes) used by businesses, which were often large enough to fill entire rooms.

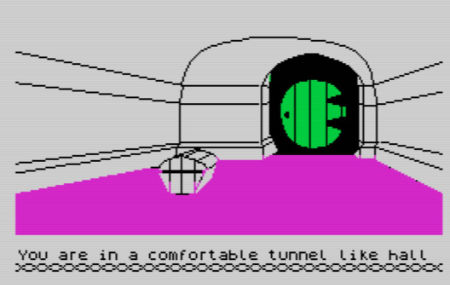

Computers in the 1980s were also a lot slower than modern computers, and had a lot less memory. The ZX Spectrum came in two memory sizes, 16k and 48k, where ‘k’ is short for kilobytes, or thousands of bytes. Nowadays, computers are more used to handling gigabytes (thousands of millions of bytes) and terabytes (millions of millions of bytes), and this has probably increased by the time you’re reading this. To give an example, this graphic is 48k:

You wouldn’t be able to fit that graphic into a 48k Spectrum’s memory, because to do so, you’d have to overwrite the Spectrum’s operating system, after which it wouldn’t be able to do anything but sit there, not even showing the graphic on the TV it used for a display.

(And if you’re wondering what size hard drive a home computer might have, the answer is none. They didn’t have any internal storage apart from their memory.)

Another thing that made computers in the 1980s different is that they were exciting. They were exciting because nothing like them had been so widely available before. And unlike most pieces of consumer technology — say, a video recorder or hi-fi stereo — which were designed to do one thing, computers allowed you to do lots of different types of things.

Mostly useless things, it has to be admitted, but it was often fun — or at least instructive — getting them to do them.

You could, for instance, use a computer to make music. Not very good music, but music all the same. “The ZX Spectrum can make sounds of an infinite variety,” it says (and, let’s face it, somewhat overstates) in the ZX Spectrum manual. The ZX Spectrum user manual is perhaps the only computer manual in history to prove its computer’s music-making abilities by having the user type in a program that plays a funeral march:

You could also use computers to learn to program. In fact, you had to learn to program at least a little bit, otherwise the computer would just sit there doing nothing.

You could also use them to play games.

Let’s face it, that’s what most people did. Home computer games were often based on — if not blatantly copied from — arcade games. Arcade games were designed to keep you interested enough that you kept wanting to play, but difficult enough that you had to keep paying out for another go when you got killed. Home computers games were similar, but, aside from the initial layout for buying the game, you didn’t have to keep paying out. Nevertheless, they kept up the arcade game philosophy of addictive play combined with a high fatality rate. Which was why, as soon as a new game came out, the question on most prospective player’s lips was, “How do you get infinite lives?”

Another thing with computers in the 1980s was that, for a brief period, there was a level playing field in game programming. A kid working alone in his bedroom with a £100 home computer had, effectively, the same resources as a large software house. And he probably had more enthusiasm, equal programming abilities, and no sense of commercial risk. Which is why a lot of weird, zany, fun and silly games came out for the ZX Spectrum, full of surreal and/or schoolboy humour, like the mutant telephones and killer toilets in Manic Miner.

So, for a kid in the 1980s, for a while it felt like you were playing games made by people like you, with a similarly silly sense of humour.

Games felt like part of your culture.

Copyright © 2017 Murray Ewing.

ZX Spectrum-7 font from www.styleseven.com