I, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, am going to Hell. All men know this of themselves, but how many can claim to have seen with living eyes the Hell to which they have been assigned? To have strolled through it, even, in the company of that being to whom they owe their damnation? More, to have themselves designed it?

I am an architect, a restorer of antiquities, and a printmaker. If you are not one of my fellow countrymen, you will know me best by my famed Views of Rome, those fantasias of ancient glory and the sad ruin of the current day, which have brought so many Englishmen and Frenchmen to my beloved city. You may have even bought one of my restored antiquities, thus taking a little of my beloved city home with you. But, as to the first named (and dearest) of my three professions, let me confess this now: it is only in this, the year of Our Lord 1766, at 46 years of age, that I have received my first architectural commission. It is a mere renovation, of a minor church. Yet I know it will also be my last, my only true work in the great art to which I have dedicated my life. I know this because I was told so by the man — if man he can be called — who commissioned a much grander work from me, many years ago.

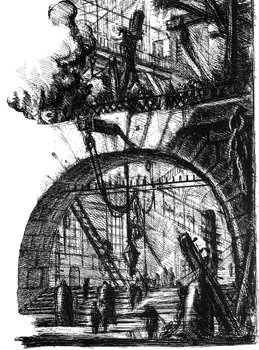

Then, the year was 1745. I had just had published, through the press of that ignoramus Jean Bouchard, a capriccio entitled the Carceri Invenzione, a masterwork of the darker possibilities inherent in architecture, in fourteen large plates. I have since been told, by the many Englishmen who seek me out because they have seen it, that this work of mine represents something new in the human spirit, a mixture of the light of our new-found reason turned upon the darkness of our mortal damnation, a harking back to what they like to call “The Gothic” — these Englishmen, how they love their fantasies of the medieval, how they love their “Sublime”.

I had been talking to Bouchard — arguing, it is true — as to the proper promotion of my new work, while also speculating to myself how I might acquire a printing press of my own (I now have one, twenty years later) so as to take on the whole business, and profit, of publication myself. The discussion, like a liquid naturally seeking its lowest resting place, descended, as ever, to personal matters. I had misspelt Bouchard’s name on the title plate of the Carceri, rendering it “Buzard”, and I was having difficulty convincing this annoying Frenchman it was not some derogatory slang of my native tongue, meant as a veiled insult.

We had reached our usual point of exhaustion on this topic, and I was about to go, when Bouchard said, having obviously held it back to be delivered as an afterthought, “There is a man who has been wanting to talk to you, Piranesi. A commission, I believe.”

“Architectural, I assume?” I said eagerly. I was always too ready, young and as yet un-disillusioned as I was, to believe my destined career was only waiting for the right moment to fall into my hands.

“How do I know? He saw some prints of yours and asked for you. He’s come back once or twice. I said you might be here today. Linger a little outside, if you wish, and you may meet him.”

Meet him outside I did, as if Bouchard’s mention had conjured him from the crowds on Rome’s crumbling streets. Dressed richly, cloaked and heavily jewelled, he was evidently a wealthy man.

“You are Piranesi?” he said.

I bowed low. “Your servant, my lord.”

“My name is Angelo Straniero. I have been looking for you.”

“And I have been waiting for you, for but these few moments. Tell me, my lord, how am I to address you?”

He smiled darkly. “I am in my secular garments, so for now we will use secular titles. Continue as you have been. It is fit.”

“My lord,” I said, with yet another bow. I have to say, though, that as I spoke the words it felt somehow wrong, as if I were being invited to commit a blasphemy. But I put such thoughts aside — I have my dark moods, and handle them as I must, or how else would my Carceri have ever been produced? As to the name, it was obviously assumed, but this “Foreign Angel” had money, so I would listen to his proposal.

“You are an architect, Piranesi?”

“I am, my lord.”

“I have seen some of your work — some of your speculations, that is. Your prints. Where can I see one of your completed projects?”

My head, still bowed, became hot with anger and embarrassment. This was how all my conversations with prospective clients started, and ended. “As to completed projects, my lord, as to actual buildings, I have as yet to see — that is, to be fully commissioned—”

Straniero cut through my stuttering with the harsh bark of his laugh. “It is of no import, Piranesi. I want you not for your past accomplishments but your present vision. What work I have seen is enough.”

“And which of my works, may I be so bold as to enquire?” I had published several theses on renovation within Rome, as well as theoretical treatises on architecture.

“These,” Straniero said, and produced from the sleeve of his robe several rolled up prints.

“They are my Carceri,” I said, frowning. “They are capriccios, inventions, deliberate exaggerations of the oppression and gloom suggested by the idea of a monumental prison. My lord is surely not intending to build a dungeon of such vast dimensions?”

This had been spoken lightly, as a jest, but Straniero’s eye held mine with a flat determination. “Is the world not stocked enough with sinners to fill a hundred such labyrinths to capacity?”

“Yes, my lord,” I said quietly. “It is.”

“My problem, Piranesi, is that these views you have produced are not complete. They sketch mere points in a far vaster construct. They suggest, they evoke. But they cannot be used to build this magnificent prison you have envisioned. They do not join up.”

It was at this point I decided the man I was talking to was insane. But I stayed, weak as I am, because of the glitter of gold on his fingers.

“What I would commission from you, Piranesi, is some further views. We have fourteen here, so let us say a further thirteen are required to indicate how what we already have is to be properly joined together. Yes, thirteen. It is a number I like.”

“Very well, my lord,” I said, carefully. “But I have several commissions—”

He cut me off by producing a fat, jangling purse. “Here is the first payment. Bring me thirteen views and you will have three times this again.”

How was I to contact him? Through the printer Bouchard. I later asked Bouchard, but the Frenchman knew no more about Angelo Straniero than anyone else in Rome.

The purse, once its coin had been counted (and tested, with more than just a bite), sat on my table for the rest of the day, and I sat before the table, staring at it. It was genuine money, and I was in need of it. If Straniero was merely half deranged, he might well pay the additional sum, as promised, on delivery of the required sketches. As night fell, the suggestion worked upon me. Flashes, as of lightning on that dark, skyless region in the deepest recess of my soul, showed me just such visions as Straniero demanded. They came to me as a coldness or a fear, a fever of solid masonry and shadow more solid still, a pressing lust of chains and ropes, of mass and darkness. I worked quickly, in a sweat, so that the red chalk in my hand smudged with the drips from my brow. By morning, I had inked four views. I kept my shutters tight and worked through the day, and again through the night. I slept fitfully a bare few hours, then delivered my message to Bouchard.

“He has just been here, asking for you,” the Frenchman said. “With luck you might catch him outside.”

I had not seen him on the way in, but as soon as I left the printer’s, I found Straniero in the street.

“You have the sketches?” he said.

I handed them over.

He unrolled them, nodding, letting out the occasional sigh or tut of pleasure. “Piranesi, you have excelled yourself. This work will earn you a place in eternity.”

Somehow I resented this exaggeration more than anything else about the man — his evident derangement, his pretence that these sketches were to be used in building what I had drawn, my need for his money, my having to bow to him while he lied to me.

“You have the payment, my lord?”

He handed over a large purse casually.

My resentment and self-disgust broke free. “My lord, you ordered these drawings as an architectural commission?”

“Yes.”

“So they are to be constructed?”

“They are.”

“Am I, as architect, to oversee their construction?”

“It is not necessary.”

“Do you require details of the inner support of, say, the round tower, the drawbridges, the staircases?”

“My workmen are skilled enough, Piranesi. What was required from you, the vision, you have provided.” There seemed to be a hint of warning in what he said, as if he were telling me to leave be. I ignored it.

“My lord, am I at least to be allowed to see this fantastic work when it is finished?”

“You really want this, Piranesi?”

“I do.”

He smiled that dark smile of his. “Then await my word, Piranesi. Await my word.”

How long would it take a man to construct, in stone and iron and wood, the vast fantastic dungeon pictured in my Carceri? It is pointless to ask, for what man has the resources? Even His Holiness the Pope — but I cannot make the comparison between that great man and Angelo Straniero.

It was twenty years before I heard again from my former patron. If I heard from him at all, for sometimes I doubt — but, no, I cannot doubt. It was real, despite the fever in my brain. I would never fear a mere dream so.

It was indeed a fever that took me, that confined me to my bed and filled my head with dark feelings. I seemed to hear a single word again and again, obsessing over it as one does in a fever, hearing it as if spoken by a hundred tongues, feeling it breathed upon my heated skin by every draft and breeze. The word itself — I will not mention it now — somehow recalled Straniero’s parting remark. I remember crying out, among the many other things I muttered in my fever, “Is this the word I must await?”

Suddenly he was there, in the room, before me. He had not, of course, aged in all those years.

“Piranesi,” he said, “it is finished. You still want to see it?”

“I do.”

“Then rise and follow me.”

I rose, and somehow the cold of the sweat on my skin left me. I do not remember our journey in detail, only that Straniero led me from my room and through my home without attracting the attention of anyone there. We mounted a carriage, there was a nightmare of jostling, darkness and discomfort. I mumbled questions, broke out in pleas for us to slow or stop. There was a great heat. Then Straniero said, “We are here.”

We were standing, alone, on the level slabs of a courtyard. The carriage had left us, and I did not look behind to see where it had gone, for before me was a vision I had once had, a caprice I had set out in chalk and ink and had printed on the press of Jean Bouchard. But now it was real.

“My Carceri,” I said.

A little in front of us, a broad flight of steps rose some way under a heavy stone arch. Loops of rope, hung from iron rings as large as a man’s head, festooned the stonework like the sad remains of rotted floral decorations. In one place, an enormous diamond-shaped lantern hung, spreading a nimbus of smoky red light. Weak as this light was, there was somehow enough to see further, much further. Not just through the arch, to the gallery beyond, but upwards, ever upwards, to where pillars soared and great monumental buttresses curved between wall and ceiling. I saw the wooden railings of countless walkways, and staircases angling between them. I saw heavy iron grilles and barred windows set in thick stone walls. I saw the unforgiving right-angles of gibbet-like struts of wood, adorned with spikes, draped with ropes. A sudden shrill blast of steam, billowing in a cloud from a nearby grille, called my attention to the echoes in that place. They were without number. Every sound called forth a thousand ghosts to whisper itself back, back, back to you from every corner and curve in the infinite labyrinth that was before my eyes.

I felt a hand on my arm.

“Is it not as you imagined it, Piranesi?”

“Yes,” I said, with a breath, “but so much more.”

Straniero urged me forward.

The floor between us and the flight of steps was dotted with tall bollards, bell-shapes of stone higher than a man, topped with iron rings, from which depended chains with links as thick as my wrist. In one corner there rested several massive beams of wood, each one fretted with bars of rusted iron. They suggested not so much the remains of construction work as the possibilities of improvised tortures.

How can I begin to describe the feelings that filled my breast as I walked with my guide through this thing I had designed? Dare I say that pride was among them — pride as well as awe, and fear, and an oppression born from the weight of all that monumental masonry, all that shrouding gloom? This was my creation, realised in stone, and wood, and iron. Yet — what manner of man would create such a thing — could create such a thing, so heavy with dark, incarcerating fatalism, with foreboding, with sin? Who but a doomed and damned man?

At this thought, my perceptions began to focus on the details, and my mind began to dwell on such questions as what purpose this vast construction could serve, and the manner in which it might achieve its purpose. As we came to a spiral of steps and began to climb, I said, “That spiked machinery we passed—”

“It is as you drew it, Piranesi.”

“Yes,” I said, “but it had not the look of such horror, before.”

“That is because it had not the reality.”

The place was alive with the creak of wood, the shush of steam, the crack of straining pulleys, the slap of rope on rope in the uneasy air. Each of my footsteps sent its timid pad on a journey far into the maze, only to come back, repeating itself defeatedly, like a forlorn messenger reporting its failure to find an exit.

I asked, more than once, “Straniero, what is this place?”

But always he failed to reply, directing my attention instead to the architectural fantasia around me. Doors so high they dwarfed us, spiked and barred with great slats of crude-wrought iron. Rafters supporting random wooden platforms, reached only by skeletal ladders, or winched ropes. Spear-headed flagpoles, like the knightly lances of giants, hanging sheets of rotted canvas over our way. The military trophies I remember drawing at the headway of so many flights of stairs seemed empty, mocking, somehow evil, the collapsed remains of gargantuan soldiers.

“There are no people,” I said, as we came to a dark opening framed by coffin-sized blocks of stone. I said it with relief, and wanted reassurance. “In my drawings, there were people.”

“I took the figures to be mere suggestions of scale,” Straniero said, smiling, as ever. He cut short any further questions with a nod. “Look up ahead, Piranesi. The Wheel.”

I could not help but gasp as the hall opened before us and that vast machinery I had sketched so lightly, so quickly, and with such a thrill of caprice, a pride in my daring and invention, became real before me. Clouds of steam caressed its giant curve, its massy struts and supports. Its weight, its solidity, its reality — I felt tears rise, despite my fear.

“Yes,” Straniero said, so close to my ear his voice was a grumble of stone on stone. “You feel it, do you not?”

“It is magnificent,” I said. “But terrible, terrible. It might be the wheel that...”

“Go on, go on.”

“...That drives the fate of man, that grinds his soul...” I turned to my guide, shaking with fear and fever and awe, and yet again asked the question that had so many times been on my lips. “What is this place? Tell me, what is it?”

“Piranesi, you designed it.”

“But what is it? Where is it? Who are you?”

“So many questions. And if I were to answer just one?”

I fell before him, gasping out what I most needed — most dreaded — to know. “What manner of sinner would be consigned to such a — such a Hell as this?”

That word. That word. It was the word I had been told to await. The word that had haunted my fever, that had called me on this journey. The word I had dreaded to speak but knew it belonged, as no other, to this place I was in. And with it, had I not answered myself?

Straniero took a breath and sighed as he surveyed the mass of stonework above us. He smiled calmly, a gardener who has done his work and now sees, with patient satisfaction, nature’s compliant response. “This place, Piranesi, is a special annexe of my domain. It is meant, all this vast space, for one man alone. For I have an infinite amount of space, Piranesi, and so many sinners, each in need of his special niche.”

“How long?” I said. “How long must I — must he — this sinner, this poor sinner — dwell within such a nightmare?”

“Why, for eternity, Piranesi. For eternity.”

Some spark of boldness, some cinder-worm of arrogance, lit within me as I stood in that Hell before the creature that called itself Angelo Straniero. This, I remember thinking, is the Devil, and deals can be made with him as they cannot be with God. For what loyalty have I to a God who gave me the desire to be an architect, the ambition, the pride, yet left no space in my fate for the realisation of that desire, the answer to that pride? What love could such a God have for the insect Man? And if I cannot have the love of God, shall I not then welcome the damnation of His Adversary?

“Straniero,” I said, “I have all my life longed to be an architect.”

“And you see before you, Piranesi, your work realised in stone. It will stand for eternity.”

“But,” I said, “in the world, among men — tell me, shall I ever achieve my desire, even once?”

Straniero paced a little away from me. When he turned, his face was half in shadow, as if he were melting into the thing he truly was. “In your life, Piranesi, you will only ever have a hand in your final resting place.”

My present commission, the renovation of the Church of Santa Maria Aventina, was placed in my hands by Pope Clement XIII. (I note that number, which Straniero so liked.) The work I do will earn me the title Knight of the Papal States, as well as a place, when I die, within that venerable temple’s crypt.

My final resting place. Is this what Straniero meant?

No. The renovation, though prestigious in its way, is not a true architectural project. I am merely building upon another’s work, bringing back from ruination another’s time-crumbled vision. In my life, I have designed but one project that achieved realisation, and it will be my final resting place. Not of my mortal remains, but of my eternal. As promised, I will wander the galleries and walkways of a nightmare I once had, a vision I once scratched, in fevered lines, upon large sheets of paper, and etched on printer’s plates. Will I, then, feel satisfied that I have achieved my dream, my desire as an architect? Perhaps eternity will teach me to forget the disappointments of this life, and accept the fulfilment I have been offered. Perhaps this much I will have.

Recently I have set to work again on the plates of my Carceri, prior to reissuing them through my own press. I do not have the thirteen I gave to Straniero, but they are not needed. I added two more, intending to add others, but soon realised it was not the breadth and variety of view that was lacking in those drawings of twenty years ago. The essence of what I witnessed on that fevered night is present enough in the original work. All that is required is a little more solidity. Having seen the thing in reality, having felt the weight of its stone, its darkness, I find myself returning to those original drawings and scoring over the once-light lines again and again, making them solid, making them heavy, making them dark.

It is what I saw. It is what I knew. It is what I will know throughout my lone and endless damnation.