By Murray Ewing. Originally published in Cybernet2000 #10, Feb 1998

(Note: This article was written in 1998, when the Star Wars saga only consisted of the first three films. It’s presented here for historical interest.)

When you watch a fantasy film, you enter into a sort of contract with the film-maker. You are promising to believe what he shows you, and he is promising to provide something which, while it isn’t necessarily realistic, at least keeps its illusions consistent. Coleridge called it “suspension of disbelief”. The trouble is, disbelief isn’t easily suspended, and just one glitch — a monster with a zipper down its back, a spaceship with strings attached, someone falling the wrong way when they roll the camera for space-turbulence — and the bubble will burst. Star Wars was so successful because it fulfilled its part of the contract as did no other fantasy film before it.

I’m not only talking about the effects, although Star Wars did invent the modern effects-movie. It also works purely as a story. Star Wars, as with any fantasy film, created its own universe — but it did it brilliantly.

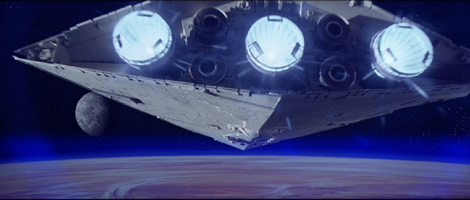

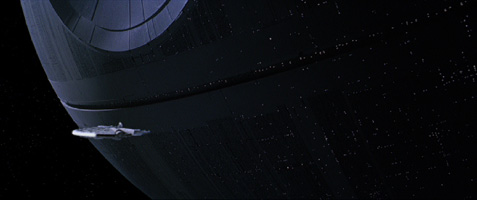

What’s more, it did it so casually. Yes, it could be breathtaking, as it was with the opening shot of the enormous Star Destroyer flying overhead (a sight greeted by thunderous applause as its first showings), and the fast and furious TIE Fighter/X-Wing dogfights around the Death Star. But it could also have battered old robots tottering around a junk yard before being sold like second-hand cars, and rusty, patched-up hoverspeeders, and laser swords dismissed as the stuff of legend, and weird-looking aliens that could be nonchalantly chatted to in a seedy bar. George Lucas called it “used space”, and you could believe that it had been lived in for centuries — not just created the moment the film started, and dissolved the moment it ended (take a look at any bookshop, video shop or computer shop, and it’s obvious it has refused to fade at all.)

The only other work of fiction I can think of that is so consistent and detailed is The Lord of the Rings. A recipe for success, perhaps?

The fact that it exists at all can be attributed to three people. First and foremost is, of course, the writer and director George Lucas, the whiz-kid film student from USC who had, at the time, only made two professional films: THX 1138, a downbeat, dystopian SF, and American Graffiti, a nostalgic film about his own cars-and-rock’n’roll youth. The second is the man who would work as his producer, Gary Kurtz. When they decided to get together to make a Flash Gordon-type film, Star Wars was born. Lucas locked himself away and began the painful process of writing it. He came up with a story that was three times as long as it needed to be and so, instead of cutting it, merely took the first third and filed the rest away, with the vague idea of making a trilogy.

What Lucas and Kurtz needed now was money, and the only way they were going to get that was by infecting someone else with their enthusiasm. That someone else was Alan J Ladd, head of production at 20th Century Fox. Fox, at that time, was at a bit of a low ebb (along with the rest of America’s film industry), and they certainly couldn’t afford to gamble on a science fiction film — a genre which had not had a commercial success in years. It was only Ladd’s enthusiasm that got it accepted at all. Even then, Star Wars was treated as a low budget film. The contract that Kurtz and Lucas signed with Fox was almost dismissive. Among other things, Fox didn’t even bother to secure merchandising and sequel rights simply because they thought them worthless. It was one of the worst mistakes in commercial history.

The filming of Star Wars was marked by a string of disasters. When the film crew set up in Chott el-Djerd in Saharan Tunisia to start filming the Tatooine sequences, it began to rain for the first time in fifty years. The crew was struck down by dysentery and pneumonia. The ninety-foot-high sandcrawler prop was blown down by desert winds, and remote-control droids regularly went haywire.

Things didn’t get any better at the studios in England, where unions insisted that all filming stop at five-thirty on the dot, pushing the film further and further behind schedule, until, in the last week, three separate crews had to be used to get it all finished on time. By that time, because the technology was still being developed, not a single effects-shot had been completed, and the cast were beginning to think they were working on a turkey.

Worse was to come. Lucas had to reshoot the cantina sequence (with more monsters), and the landspeeder sequences, and it was only Alan Ladd’s belief in the film that got him the extra cash. Then Mark Hamill was involved in a near-fatal car crash, and the shooting had to be rescheduled. Test screenings, with black and white footage of World War Two dogfights in place of the still-unfinished space-battles, started the rumour that Fox had a failure on its hands. So sure was the industry of Star Wars’ imminent turkeydom, that rival studio executives started to buy up Fox shares, expecting them to plummet and enable a boardroom takeover. Cinemas refused to book the film, and Fox resorted to (and was fined for) a sort of blackmail to get them to take it. On its opening day, Star Wars appeared in only 40 theatres.

It was the biggest opening in history.

Over the first week, it averaged $10,000 per cinema, per day. That was double the figures for Jaws, the previous year’s success, and the only thing comparable. Cinema managers had to change their policy because of the film. Previously, buying a ticket enabled you to walk in and sit through as many screenings as you liked. Now, they had to empty the theatre after every showing, just to alleviate the enormous queues that formed wherever Star Wars was showing.

And then there was the merchandising. Fox would never again throw the rights away so casually. John Williams’ soundtrack became the first orchestral album to enter the US national charts. Toy company Kenner would sell one billion dollars worth of Star Wars toys per year for the next seven years. To cap it all, Star Wars was nominated for ten Academy Awards. It won seven.

Star Wars has often been dismissed as unoriginal. In preparing for the writing of Star Wars, George Lucas read up on SF classics new and old, and it tells. For example, in the first book of E. E. “Doc” Smith’s Lensman series (which Lucas read) the hero comes across an artificial Death Star-like planet, used as a base by and evil alien. And the sandminer could well have come from Frank Herbert’s Dune. Parallels can even be seen with such works on untechnological fantasy as The Wonderful Wizard of Oz: C3PO is the Tin Man, Chewbacca is the Cowardly Lion, Darth Vader is the Wicked Witch, Ben Kenobi is the Wizard of Oz, and R2D2 is Toto. But to see only this is to miss the point.

One book which Lucas kept beside his desk while writing the initial storyline was Joseph Campbell’s Hero With a Thousand Faces. It is a book about mythology, and it stresses the fact that there are not many myths but just one, which it calls “the monomyth”. Campbell’s ideas applied themselves easily to stories of all types (Christopher Vogler has written a book, The Writer’s Journey, which applies them specifically to film).

Fantasy has never been ashamed of the fact that it is telling a story, and Star Wars seems to flaunt it. Such details as the characteristic way the film fades between scenes, with one scene wiping over the other from the side or the top (a technique taken from one of Lucas’ favourite films, Kurosawa’s Hidden Fortress) has the appearance of a page in a storybook being turned. And John Williams’ score adds further to the story atmosphere. He used the Wagnerian technique of having a short musical theme or “leitmotif” for each of the main characters, as well as for other concepts such as the Force and the Empire. This is used to emphasise the importance to the story of any particular moment — an example is when Luke makes his first appearance. The first few bars of the main theme are played in a quiet, subdued manner, and the viewers immediately know that this is their hero.

Fantasy is also closer to pure story than other genres. The concept of the Force in the Star Wars films makes this clear. Just what the Force really is, is left open to interpretation. It could be mystical, or psychical, or it could be a metaphor for the general power of people to do good or evil. It is a point in Star Wars’ favour that “good” and “evil” are never given anything but a human form — there is no God or Devil in the films, only human beings.

With the release of its sequels, The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi (originally titled Revenge of the Jedi until Lucas realised that “revenge” was a thing only the Dark Side did), the Star Wars phenomenon continued to break records and remake the world of entertainment in its own image. The fact that it could then come back 25 years later and do the same thing just proves its timelessness. And now another three films are to be made — prequels to the original trilogy — with the promise of another three, these being sequels, after that. Whether they will equal the success of the first three films is something only time will tell — and one thing Joseph Campbell points out is that the monomyth must constantly change its appearance — but, for now at least, Star Wars refuses to die.