Dunraven

1887

Punch, February 19, 1887, p. 93

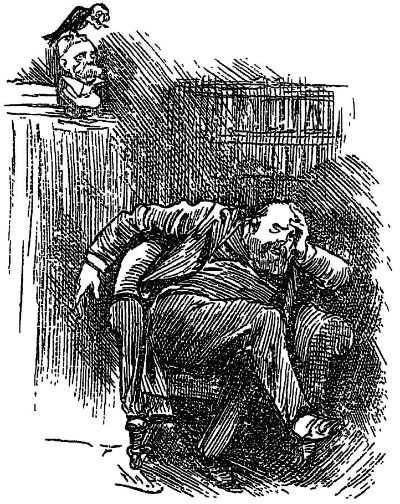

Cartoon from Punch

Perplexed Premier loquitur[3]:—

Once upon a mid-day dreary, while I pondered weak and weary

Over many a Blue Book[4] dull, and tome of diplomatic lore,—

While I nodded nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping

As of someone sharply rapping, rapping at my office door.

“’Tis some diplomat,” I muttered, “tapping at my office-door.”

Only that, and nothing more.

Open then I flung the doorway, when, with blast like one from Norway,

In there bustled brisk Dunraven, whom I’d often seen before,

Not the least obeisance made me; for no greeting stopped or stayed he,

But with solemn mien and shady, perched above my office-door.

On a bust of Randolph Churchill,[5] just above my office-door—

Perched and sat, and nothing more.

Then this pompous bird beguiling my tired fancy into smiling,

By the proud pragmatic aspect of the countenance it wore,

“What’s your little game, Dunraven? Surely you have not turned craven.

“Back of late to a home-haven fresh from many a foreign shore—

“Say if travelling your small game is, are you off to some far shore?”

Quoth Dunraven, “Nevermore!”

Startled at the stillness broken by reply to aptly spoken,

“Doubtless,” said I, “what it utters is its parrot stock and store

“Follows fast and follows faster. Well, it is a beastly bore.

“But I’ll tune my harp to Hope, stout Hartington,[8] at least, is sure;

“He will leave me—Nevermore.”

But Dunraven still sat smiling in a manner rather riling;

So I wheeled my office-chair in front of bird, and bust and door,

And upon its cushion sinking straight I tackled him like winking,

And I cried, “What are you thinking, croaking, croaking, as of yore?

What the dickens do you, ghastly gloomy and funereal bore,

Mean by croaking, ‘Nevermore!’”

“Prophet,” said I, “of things evil!—this will play the very devil

“With the Union of the Unionists—a thing we both adore.

“Tell me are you too afraid, in view of an Exchequer laden?

“Can’t you see Retrenchment’s[9] Aidenn, won’t be reached still scares are o’er?

“Then we’ll seek that distant Aidenn, then together seek its shore.”—

Quoth Dunraven, “Nevermore!”

“Be that word our sign of parting, bird or fiend!” I cried, upstarting,

“Hook it with the wanton Woodcock to Algiers,[10] to Afric’s shore.

“Make no speeches as a token that our party ties are broken.

“Twice already Woodcock’s spoken,—don’t you burst into a roar,—

“Take your hook, if you must go, but spare us on the House’s floor.”

Quoth Dunraven, “Nevermore!”

And Dunraven, spite his flitting, still seems sitting, still seems sitting

On that plaster bust of Churchill, just above my office-door;

And his eyes seem ever dreaming, economic juggles scheming,

And the light within me gleaming in the good old days of yore,

Ere young Randolph came or Staffy[11] went—brave beacon-light of yore,

Shall be lifted—Nevermore!

Footnotes

- Lord Dunraven — Windham Thomas Wyndham-Quin (1841–1926), the 4th Earl of Dunraven and Mount-Earl, succeeded to his father’s Irish Peerage in 1871, with estates in County Limerick, and lands in south Wales and, later, Colorado. A Conservative politician, he was Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies from 1885 to 1886, and again from 1886 to 1887. His 1887 resignation from this position (though he remained in politics afterwards), was, by his own account, because he felt the government were about to introduce “additional powers and exceptional legislation” to deal with problems in Ireland, which he felt would needlessly complicate and damage the situation. (He was in favour of Irish home rule.) Some sources tie his resignation to other events of the time, including a dispute over fisheries in Newfoundland, and the resignation of Lord Randolph Churchill. You can read his resignation speech in Hansard. (back to text)

- Sir Henry Holland — Henry Holland (1825–1914), 1st Viscount Knutsford, a Conservative politician. He was Secretary of State to the Colonies from January 1887 to August 1892, so would have just been made Dunraven’s boss at the time of the resignation. (back to text)

- Perplexed Premier loquitur — “The perplexed Prime Minister speaks”. The Prime Minister at this time was the Conservative Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (1830–1903), who was Prime Minister from 1885–1886, 1886–1892, and 1895–1905. (back to text)

- Blue Book — Generally, a blue book is a compilation of data or statistics. In the UK government it is used to refer to a number of things, including an official parliamentary report, the accounts of the United Kingdom, collected diplomatic correspondence, and colonial reports. (back to text)

- Randolph Churchill — Lord Randolph Churchill (1849–1895), father of Winston Churchill, held various government positions including Secretary of State for India (1885–1886), Leader of the Conservative Party (1886), Chancellor of the Exchequer (1886), and Leader of the House of Commons (1886–1887). He was particularly admired by Dunraven. His being mentioned in the poem is apt because he offered his resignation as Chancellor over the funding of the armed services, expecting his resignation to be refused and for him to win the issue; instead, it was accepted, and his political career was effectively over (though he remained in Parliament). You can read his resignation speech in Hansard, for 27 January 1887. (back to text)

- Woodcock — “Woodcock” was Punch Magazine’s name for Lord Randolph Churchill (whom they also called “Lord Random Churchill”), because he was the Parliamentary representative for Woodstock, which they changed to “Woodcock” as he “really represents the ‘Cocky’ side of London impudence” (Punch, 9th July 1887, p. 11). (back to text)

- who so sold me — i.e., betrayed him, by speaking out against the government and resigning.

- Hartington — Spencer Compton Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire (1833–1908), was the Marquess of Hartington from 1858 to 1891. He was the leader of three different political parties, the Liberal Party (1875–1880), the Liberal Unionist Party (1886–1903), and the Unionists in the House of Lords (1902–1903), and declined the Prime Ministership three separate times. The basic stance of the Liberal Unionist Party was to oppose Home Rule (i.e., self-government) in Ireland. (back to text)

- Retrenchment — Generally, retrenchment means the reduction of public expenditure (and hence taxation). “Peace, Retrenchment, Reform” was a political slogan associated with Whigs, Radicals and Liberals throughout the 19th century. (back to text)

- Algiers — After resigning, Lord Randolph Churchill went on a holiday to Algiers from 9th February 1887, then on to Tunisia (where he heard of, and approved, Dunraven’s resignation), then Italy in March.

- Staffy — Stafford Henry Northcote, 1st Earl of Iddesleigh (1818–1887), Conservative politician, Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1874–1880, Foreign Secretary from 1885 to his death on 12th January 1887. (back to text)

Return to the Quaint and Curious index for more pastiches and parodies of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven”.